- India

- International

Why the govt has more cash, less grain to give

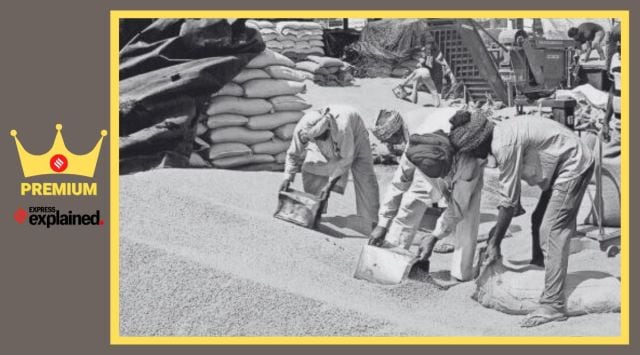

With stocks of rice and wheat finely balanced with the FCI amid monsoon-linked production uncertainties, the scope for distributing and exporting surplus grains has considerably reduced.

A poor crop last year led the Centre to ban wheat exports in May 2022.

A poor crop last year led the Centre to ban wheat exports in May 2022. Three years ago, neither the Centre nor the states had money to make large-scale cash transfers to poor and vulnerable households suffering job and income losses during the pandemic-enforced lockdowns.

But there was plenty of wheat and rice in the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) warehouses: Some 813.5 million persons received 10 kg of grain per month practically free from April 2020 to December 2022.

Offtake of the two cereals totaled 92.9 million tonnes (mt) in 2020-21 (April-March), 105.6 mt in 2021-22 and 92.7 mt in 2022-23, as against an annual average of 62.5 mt during the first seven years post the National Food Security Act (NFSA) from 2013-14 and 48.4 mt in the seven years preceding the law.

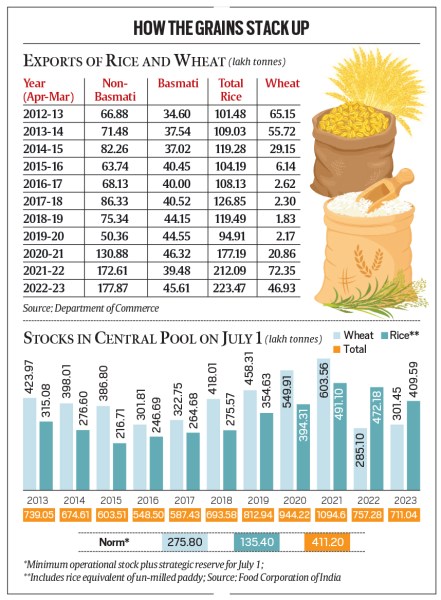

It wasn’t just the public distribution system (PDS). The three years from 2020-21 also saw all-time-high grain exports from India (see table below). Rice shipments alone aggregated 21.2 mt in 2021-22 (valued at $9.66 billion) and 22.3 million tonnes ($11.14 billion) in 2022-23, with these at 7.2 mt ($2.12 billion) and 4.7 mt ($1.52 billion) respectively for wheat. Thus, there was surplus grain not only to give out free, but even to export in record quantities.

Cash for grain

The situation is almost the reverse today. Governments have money, due to the resumption of economic activity. Gross goods and services tax revenues grew 21.9% in 2022-23 and have risen 11.6% in April-June 2023 over April-June 2022. However, FCI godowns aren’t exactly bursting at the seams.

The Centre, during the post-Covid period till December 2022, supplied 10 kg of rice or wheat per person per month to all PDS beneficiaries. From January 2023, that quota was restored to its previous level of 5 kg under the NFSA.

The Congress government in Karnataka, last month, sought additional grain from the FCI to implement its Assembly election promise of providing 10 kg of free rice per month to all members of below-poverty-line (BPL) households.

But with the Centre not permitting FCI to make available the 5-kg extra rice, it has been forced to give cash in lieu of grain. So, instead of 5 kg rice – over and above the Centre’s 5 kg under NFSA – the Siddaramaiah-led government has, from July 10, started transferring Rs 170 against the name of each beneficiary to the bank accounts of their BPL family heads.

Simply put, earlier there was grain but no money. Now, there’s not much grain, but governments have money to pay PDS beneficiaries for them to buy 5 kg of rice at Rs 34/kg.

Depleted stocks

Politically, of course, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at the Centre has little incentive to enable a Congress state government to fulfill a poll guarantee. But there are economic reasons why the Centre would hesitate to supply additional grain, even to BJP-ruled states.

Table 2 shows total stocks of wheat and rice in the Central pool on July 1, 2023 at a five-year-low. These stocks are, no doubt, more than the normative minimum, both to meet the operational requirements of the PDS for any quarter and a strategic reserve to take care of crop failures or natural calamities.

The concern, though, isn’t with the present stock levels that are 1.7 times the required minimum for June 1. Rather, it’s to do with the monsoon and the uncertain prospects for this year’s rice crop, which may have a bearing on procurement and stocks down the line. And that would be closer to the national elections in April-May 2024.

Rainfall during the current southwest monsoon season (June-September) has been normal for the country, at its long period average till July 16. But it has been deficient or significantly below-normal in major rice-growing areas, including Telangana (-24.2%), Andhra Pradesh (-16.1%), Chhattisgarh (-21%), Odisha (-23.1%), Jharkhand (-41.4%), Bihar (-32.3%) and Gangetic West Bengal (-37.2%).

The poorly distributed rain has meant that farmers had, as on July 14, planted only 123.18 lakh hectares (lh) out of the normal total 399.45 lh area under rice during the kharif (monsoon) season. The cumulative area sown was also 6.1% lower than the 131.23 lh covered during this time last year. Moreover, with El Niño – known to suppress rainfall in India – already setting in and most global forecasts pointing to its persistence through the 2023-24 winter, there is concern over the monsoon’s performance in the rest of the season.

Deficient rainfall in the monsoon’s second half can impact the production of not just the kharif rice, but even the upcoming rabi wheat crop. Farmers need groundwater tables and reservoirs to be adequately recharged/filled for cultivating the latter during the winter-spring season.

The export conundrum

A poor crop last year led the Centre to ban wheat exports in May 2022. It was followed by a prohibition on exports of broken rice and a 20% duty being levied on all non-parboiled non-basmati shipments in September.

Despite these restrictions, the last two years registered record exports of rice and wheat. Adding maize and other cereals, total exports amounted to 32.3 mt in 2021-22 and 30.7 mt in 2022-23, worth $12.87 billion and $13.86 billion respectively.

But with retail cereal inflation at 12.7% year-on-year in June and the monsoon-related production uncertainties, the Centre is reportedly considering further curbs on rice exports. Globally too, rice is on fire. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s All-Rice Price Index (base year value of 100 for 2014-16) averaged 126.2 points in June, 13.9% higher than a year ago. Parboiled rice with 5% broken grains content is currently being exported from India at $421-428 per tonne, the highest since April 2018.

India is the world’s largest rice exporter, with a 40.4% share of the global trade in the cereal, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s estimates for 2022-23. A corollary to it is that the country cannot really import rice in case of domestic production shortfalls; it can at best limit exports. This is unlike with wheat, which can be imported, especially given benign global prices because of ample supplies from Russia.

In a scenario where FCI’s granaries are far from overflowing, one cannot rule out many states emulating Karnataka in doling out cash as opposed to free grain. It’s another thing that, from a macroeconomic standpoint, the former is inflationary and the latter deflationary.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05